How to cook onions.

The hardest thing to do when you feel like you are panicking is to slow down.

It can feel antithetical, heretical, or even downright ludicrous to do so when your neurons are firing at unprecedented levels telling you, “There is something wrong, and you need to do something about it.”

And I am doing something about it: I’m turning off the radio, putting my phone on mute, and I am choosing to pay attention to something else, something that doesn’t require a rapid pace, something where I can control the outcome, or at least understand and learn from it.

Like how long I need to cook these onions.

In the same vein, I can control what I am going to write about. And save for the following nineteen words, I’m not going to say the words COVID-19, or discuss anything medical or economical. For the next 700 words or so, I’d rather focus on what’s happening in your kitchen, in your head and heart.

In my kitchen, I’ve written down every single item I had in my pantry, freezer and refrigerator: the dried Persian limes I’d forgotten about at the back of the top cupboard, the weighed portions of cooked rhubarb in the freezer, the jar of pickled quinces I made when I was faced with forty pounds of them.

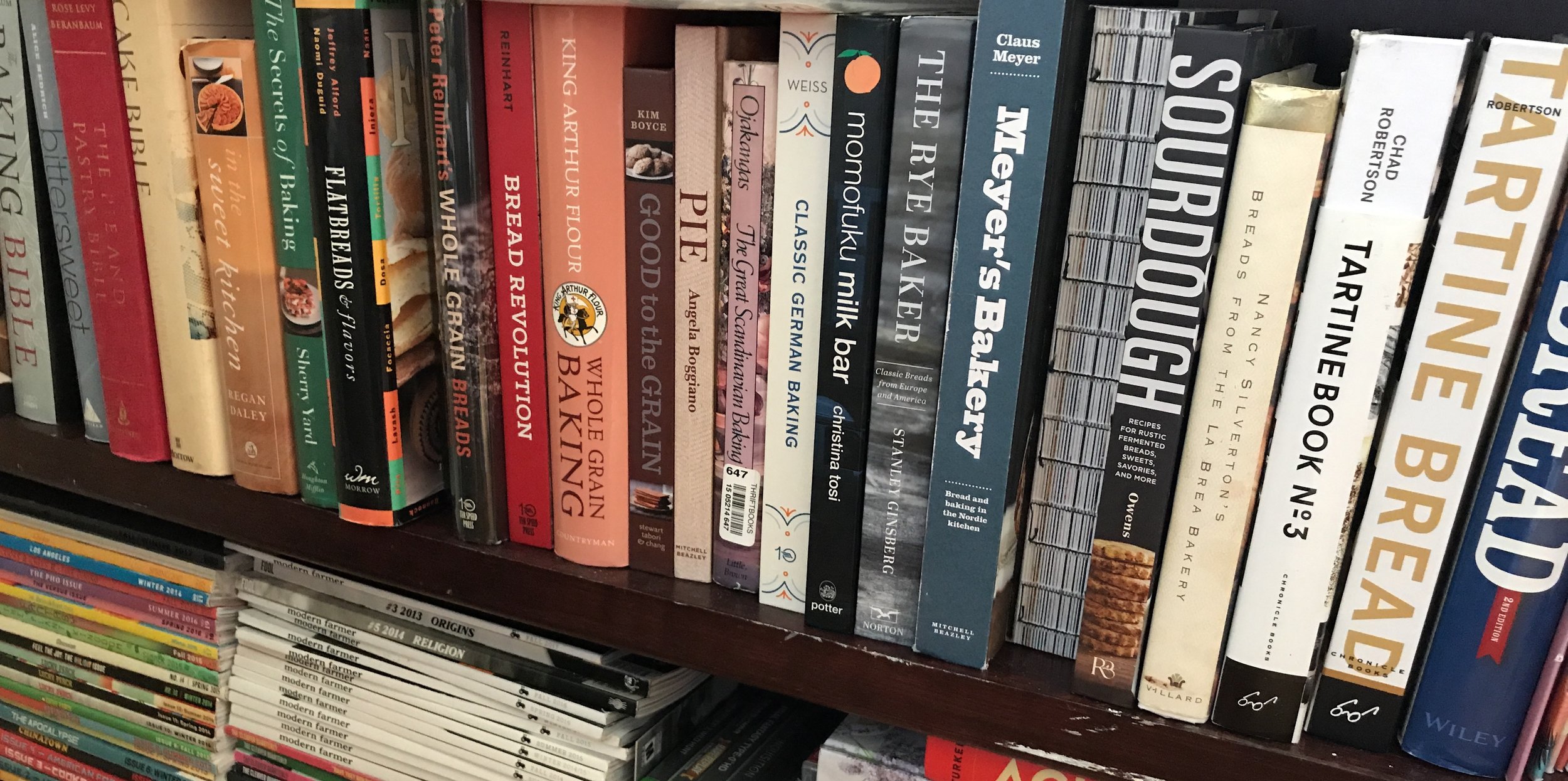

In my head, I want to weigh my options, figuratively and literally. I’ve combed through the stacks of cookbooks that line the shelves of my kitchen and living room. Cookbooks with stains on the most popular recipes, as well as cookbooks with barely cracked spines. I want dishes that will ask me to stand in front of said stove, as well as dishes that ask so little of me. I’m looking at you, rice pudding cooked in the oven. (Thank you, Nigella Lawson).

Beans for soup, stew, dips, salads. All beans, all the time.

And in my heart, I want to eat dishes made with quantities and qualities that can be happily consumed on both the day they’re made, as well as the next day as lunch or supper. Especially if that is a day that I can’t find the wherewithal to make any decisions due to being panic-stricken, let alone stand in the front of the stove and make choices about how to feed myself. My heart will need foods that soothe, and rely on very little more than re-heating.

If I can figure out how long I needed to cook the onions, then I can do those things. I can figure out what I need to cook, to please myself, to distract myself, to hone my focus on one task at a time.

Right now, these onions need a bit more salt to help them sweat.

I want to make dishes that have been waiting for me, the ones I listed on bookmarks of paper, placed within their respective cookbooks I bought over the years. Last week, it was a Turkish dish, called Pazili Ekmek, a bread dough stuffed with a filling of vegetables. In my case, I made the filling the night before, a soft savoury compote of potatoes cooked with an amorous amount of onions, seasoned with a teaspoon of smoked Turkish pepper flakes and a tablespoon of tomato paste.

I knew there was a reason I was cooking onions.

It’s the dishes I’ve never attempted before that are the most satisfying to me right now: not in the eating, but in the process, the gentle focus of my senses. The words gentle, and focus, are words I need to remind myself of.

Congee for a good day, with roasted peanuts, egg, katuo-bsuhi, and black sesame seeds.

That list of ingredients and recipes that I had collated became a game plan. Make a sponge to ferment overnight for tomorrow’s bread. Take the rhubarb out of the freezer for the coffee cake that will satisfy your sweet tooth. The leftover rice in the fridge can be cooked into some sort of ersatz congee, with a light broth made from dried seaweeds and Chinese wood ear mushrooms. It’s perfect for lunch, as all it needs is a light reheat. Maybe an egg or two, poached or hard boiled (if boiled, make extra for tomorrow’s lunch).

Right now, the most sincere, and honest thing I can do for myself is to quietly listen, and semi-intently watch these onions cook down. To feel myself slow down. To listen to the steam condense on the lid and drop back onto the hot skillet. I know (or assume? Maybe I should look at my copy of Harold McGee) that if I do this, they won’t dry out or burn as easily. These onions will become one with the rice and lentils (thank you Melissa Clark) I am cooking. But I also know my own palate, and so I am adding black cardamom to the mix, an extra bay leaf, and a little cumin and coriander to the spice mix in my grinder. Oh, and a touch of feta on top of the whole bowl, because that’s what my belly/brain/body is telling me right now. Tomorrow may be different. No, it will be different, unknown. I don’t know what I will eat, wether I will have the drive to do so, but I do know this: when the meal is ready (made fresh or reheated), a gentle voice will pipe up to remind me, “You got this. You won’t feel like you always do, and you may have a hard time sometimes. But you got this.”